The aftermath of the General Election has led to much discussion about the reliability of the pre-election polls.

One thing that is yet unknown is the potential influence the opinion polls themselves had on how people voted in relatively close contests. Were potential UKIP voters more likely to stick with Conservative candidates in constituencies that could turn Labour? How much did the “fear of SNP” holding the balance of power affect previous Liberal Democrat voters in England? Who stayed away from polls: could this have dramatically have influenced the weightings that should have been given in pre-election polling?

Having sourced results data from the BBC website [by constituency, based on AP reporting of results] and also electorate sizes from the AP website I decided to look at aspects of election voting that have not (as yet) been widely discussed. There are still some minor issues with the data – where the turnout (as reported by the BBC) is not the same as that based on AP figures for the electorate size (9 constituencies in total).

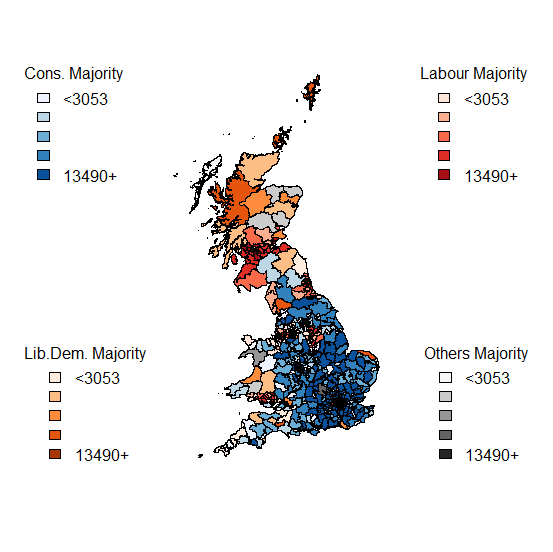

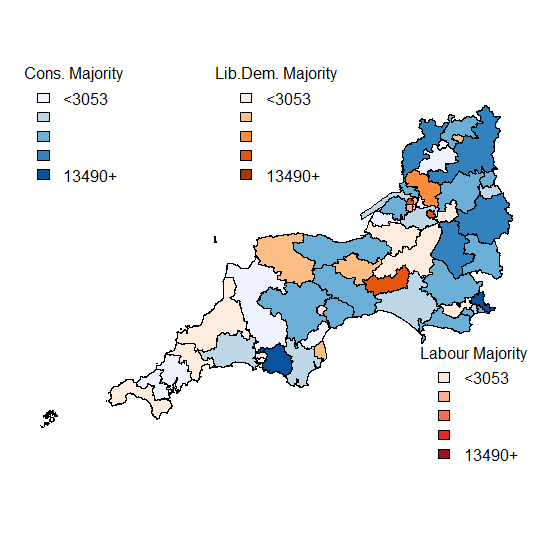

I have decided to put the mapping data to one side at the moment – lots of maps (of both winners and runners-up) abound at the moment, and detailed spatial analysis will wait until I confirm the data about electorate sizes.

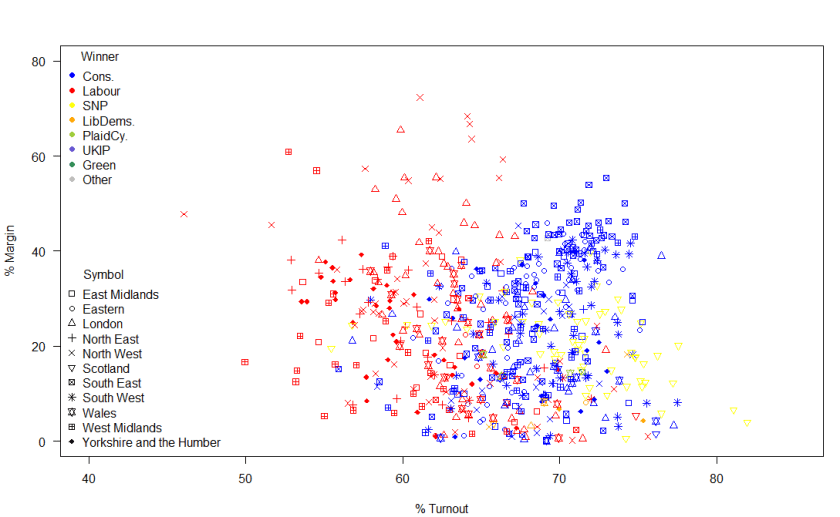

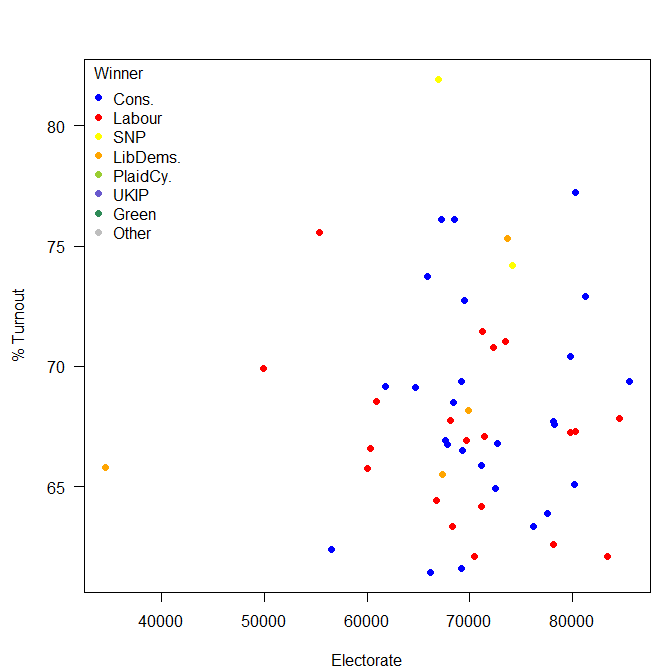

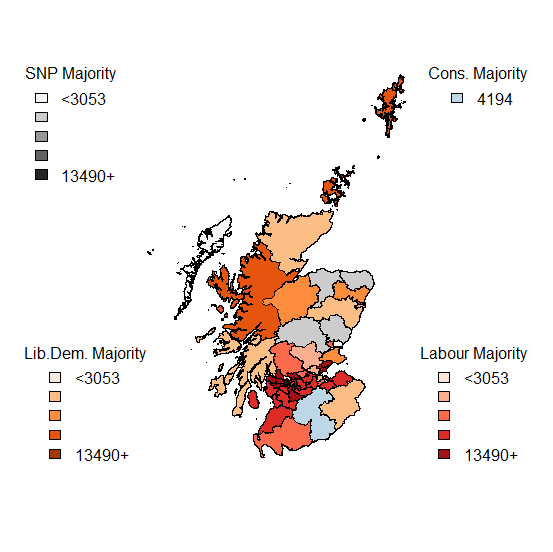

Turnout in Scotland did indicate that in the post-referendum climate, increased voter engagement and participation has continued. Compare the graph above with that of 2010 and the difference in Scottish engagement is evident.

Now looking at the margins of victory – by region and by victor.

So, what is striking about this image? Some Labour MPs had a huge margin of victory. Really a margin of victory of greater than 20% of voters is inefficient distribution of votes. Otherwise, the main talking points are the high turnout in many Scottish constituencies and the fact that the SNPs didn’t have the complete landslide of votes that their return of seats (almost 95% of Scottish seats) suggested and also that there was a much higher turnout in Conservative seats than in Labour seats.

Of the 2,909,882 valid votes cast in Scotland, the SNP polled 1,454,439 (49.98%), with Labour on 24.06%; 15.16% for the Conservatives and 7.55% for the Liberal Democrats. However, due to the First Past the Post system, the return on votes for the SNP resulted in them winning all but 3 of the 59 Scottish seats.

In Wales: Conservatives 27.25% [11 out of 40 (27.5%) seats]; Labour 36.86% [25 (62.5%) of seats]; UKIP 13.63% [0 seats]; Liberal Democrats 6.52% [1 seat]; Plaid Cymru 12.12% [3 (7.5%) of seats].

Wales is therefore a prime example of how UKIP failed spectacularly in converting votes into seats.

Before the election, there was speculation about how the UKIP vote would affect the main parties. UKIP did poll relatively well in “safe” Conservative seats – building their vote share with no direct return. The effect on the Labour vote was more direct – UKIP polled slightly better in areas that could have been marginal Labour victories [in the 15000-20000 Labour votes; the Conservatives won 61 seats, Labour won 91 seats, the Liberal Democrats 1 seat and the SNP won 18 seats] than they did in the equivalent Conservative seats. Therefore, UKIP voters had more of an influence in potential Labour gains over Conservatives than was perhaps expected.

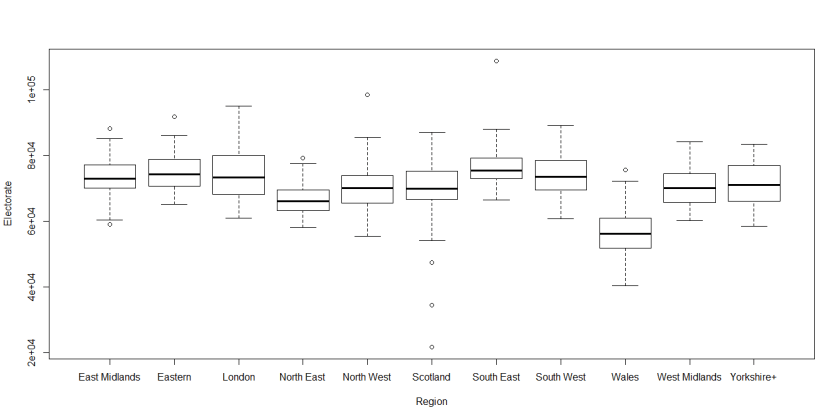

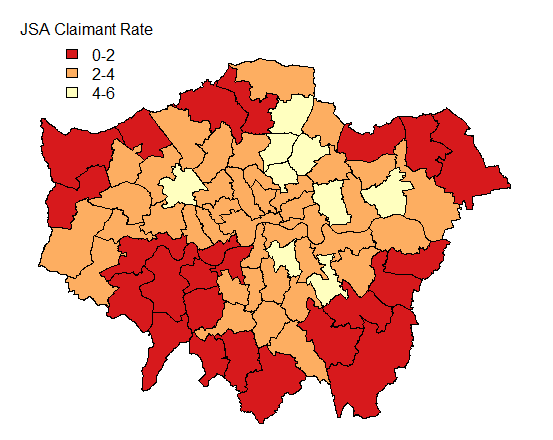

Other than the unfortunate problem of lack of proportionality created by FPTP voting, another issue is caused by the discrepancy in the sizes of the electorate. Welsh constituencies, in particular, are unusually small and may be subject to boundary changes in the future: the very small Scottish constituencies are islands which don’t lend themselves to easy mergers with parts of the mainland.

All discussions about changing the electoral system should first consider fixing the current system: the size of the constituencies is too variable to be considered equitable.

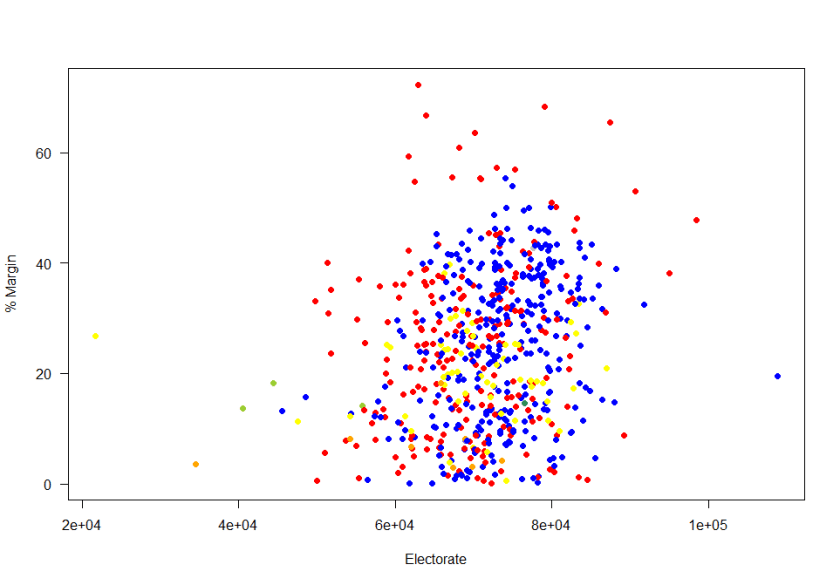

Thus the size of the margin matters in terms of the number of potential (not just actual) voters.

So who had “important” votes? Those in the bottom left of this graph: relatively small electorates in close contests. The two extremes (left and right) of this graph represent island constituencies [Na h-Eileanan an Iar is the smallest constituency, while the Isle of Wight is the largest constituency].

Looking at the constituencies where the margin of victory was less than 5% of those who voted by the size of the constituencies. Four out of the Liberal Democrats eight seats were on margins of less than 5% of valid votes. Turnout in these close seats were (on average) higher than in the seats with a closer margin: so a close race does help to encourage turnout. A “safe seat” is not a helpful thing for voter engagement.

| 2015 | |||||||||

| Cons. | Green | La

bour |

LibDems. | PlaidCy. | SNP | UKIP | Speaker | ||

| 2010 | Cons. | 295 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Green | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Labour | 9 | 0 | 209 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| LibDems. | 27 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| PlaidCy. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SNP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| UKIP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Speaker | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

The main unexpected outcome of the election was not the collapse of the Liberal Democrat vote but the extent to which Liberal Democrat seats were won by Conservative rather than Labour votes. However, this should not have been surprising, as 38 of the Liberal Democrats had a Conservative runner up in 2010. But only 17 Liberal Democrat seats had a Labour runner up in 2010.

| Runner Up 2010 | |||||||

| Winner 2010 | Cons. | Labour | LibDems. | PlaidCy. | SNP | Other | |

| Cons. | 0 | 137 | 167 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Green | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Labour | 147 | 0 | 76 | 5 | 28 | 2 | |

| LibDems. | 38 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| PlaidCy. | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SNP | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Speaker | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

Only 109 out of 632 GB seats changed parties this election. These swing seats were mainly Liberal Democrat to Conservative (27) and Labour to SNP (40). Conservatives retained 295 of their 306 2010 seats; gaining 36 from Liberal Democrats and Labour. Labour retained only 209 of their 258 2010 seats; the SNP gained 50 seats from Labour and the Lib Dems. The SNP gains were particularly noticeable as they had come second in 29 constituencies in 2010 (having won 6). In 21 of their seats that they won this time round, the SNP came from at best a third place in 2010.

So – what have we learned from all of this. The election results were far messier than many had anticipated. There is a lot of analysis to be done and all of the soul-searching about the appropriateness and efficacy of opinion polls will no doubt be of interest to many statisticians. As no preferences are expressed under the FPTP system we will never really know the extent of tactical voting in UK elections.