So, I’ve been working on sentiment analysis again. What could be more topical than analysing the tweets from the period after Trump was elected to before he was sworn in.

I downloaded Trump’s tweets from twitter in R (from the handle @realDonaldTrump)

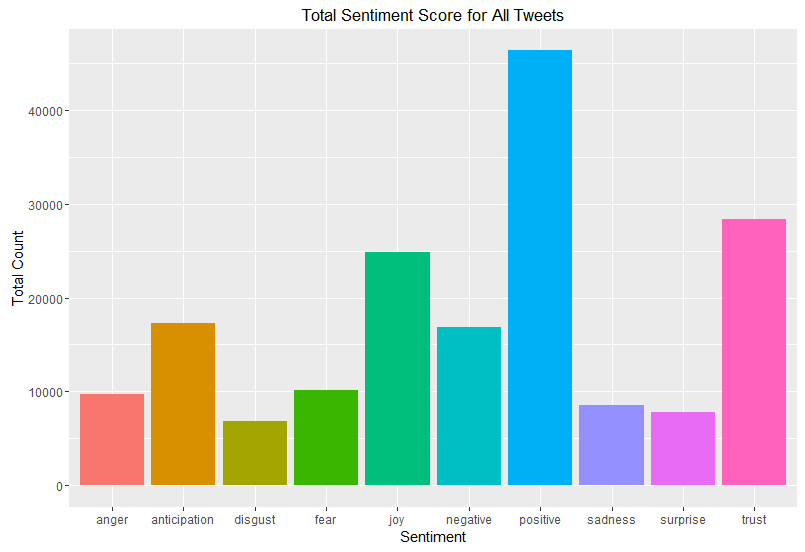

Using the syuzhet package in R it is very simple to perform sentiment analysis; with some simple manipulation afterwards, we can see the profile of the different “Sentiment Score”. A step-by-step guide is here.

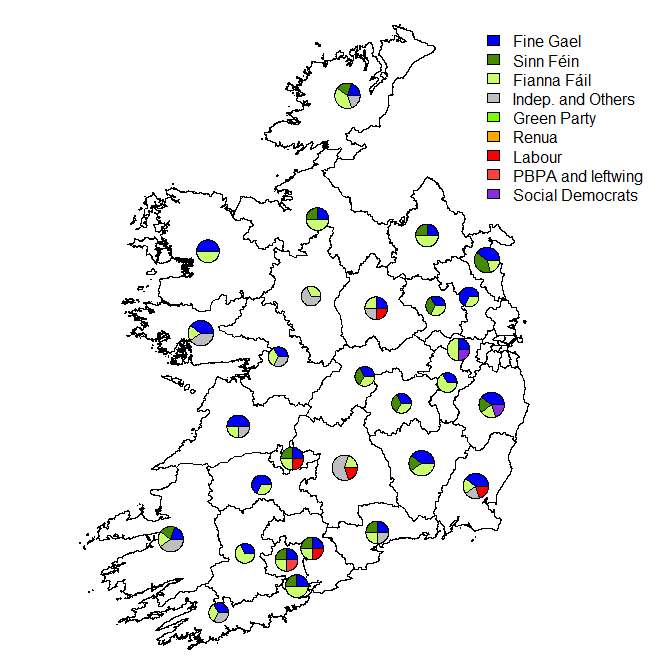

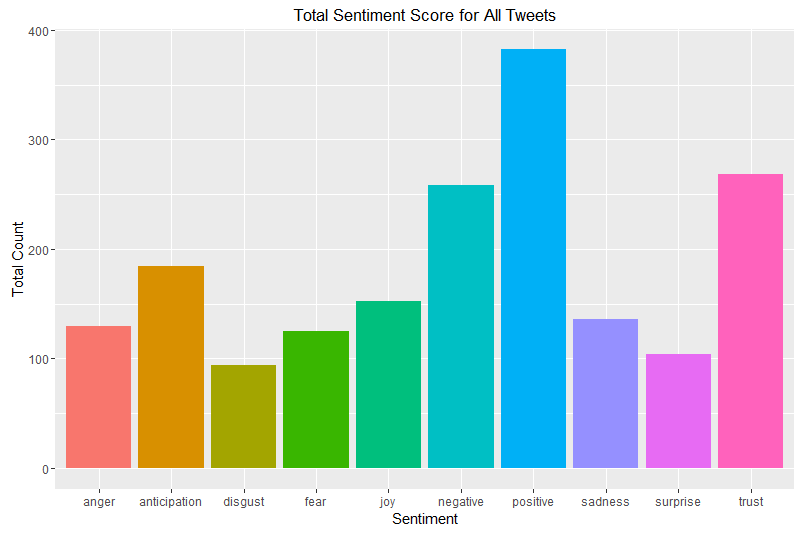

First look at the profile across all of the tweets:

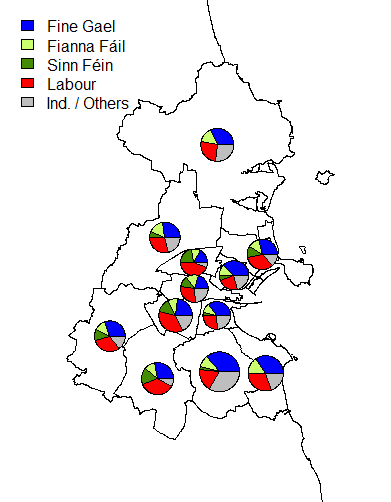

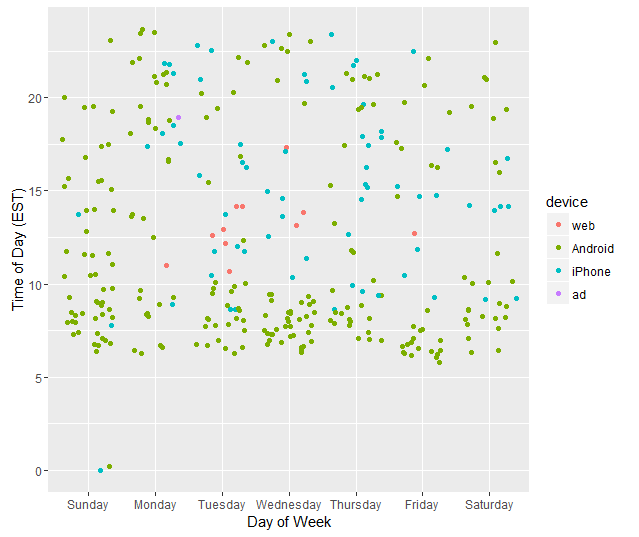

But, things with Trump are not quite that simple. It has been previously speculated that Trump’s tweets from Android devices are not written by the same person as Trump’s tweets from other sources. The general conclusion is that the tweets from Android are written by Trump himself, but tweets from other devices are written by staffers. The time of posting the tweets can be investigated to see if there are patterns:

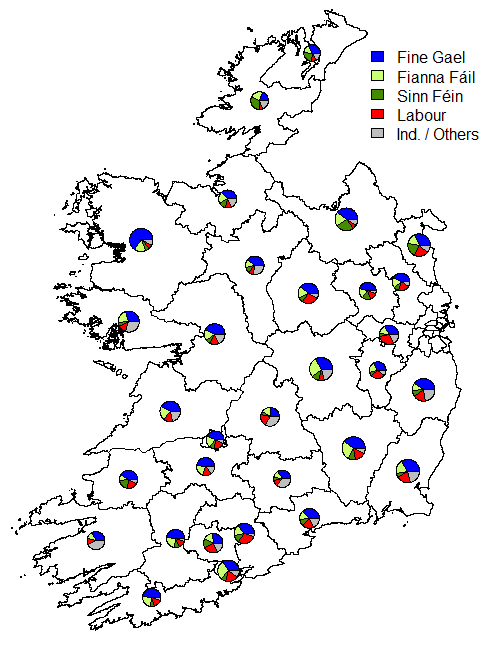

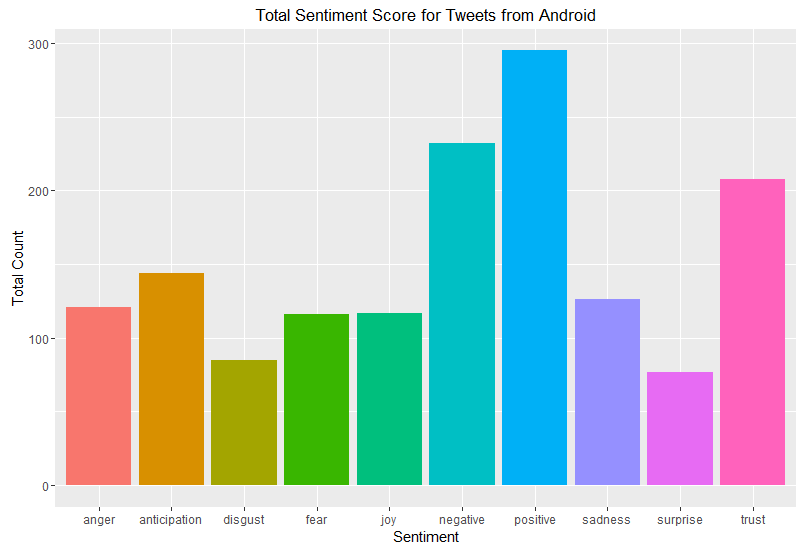

It becomes very obvious that whoever is tweeting from the iPhone is primarily active during office hours – with a few evening [18] tweets that were either thank you tweets or mentioning events that evening or the following morning. So, let’s look at those tweets written on an Android:

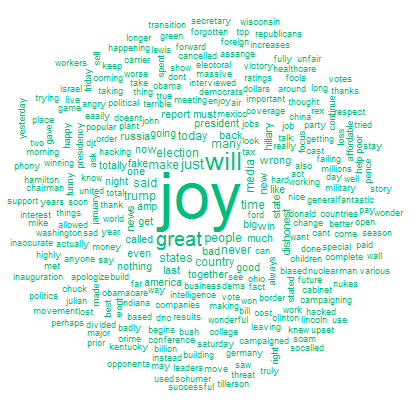

In the following sequence of wordclouds, the word in the middle corresponds to the sentiment in the graph above.

So what words were said in tweets that the sentiment analysis deemed to be angry?

Compare this to the joyful tweets:

and the tweets expressing “trust”

This process is continued for the other sentiments…

Who might be interested in this type of analysis? It doesn’t just apply to political figures; companies may be interested in the sentiments being expressed about their brands / services and in particular may be interested about the effects that changes have on what is being said online. Whether you are aware about it or not, this type of analysis is happening every day and is providing insight into how people think about a wide variety of terms.

There are limitations, of course. These include the problem of sarcasm and emojis. Automatic sentiment analysis struggles to capture sarcasm. Furthermore, emojis can be converted into text, but the additional meanings behind the emojis (think aubergine) are lost in this process!

Who knows what the future will bring as Donald J Trump has control over both the @POTUS and @realDonaldTrump accounts!

As a quick aside; here’s the sentiment captured between 21:57:57 and 22:40:31 UTC [about 5pm EST and 2pm PST] on Saturday January 21st under the hashtag #WomensMarch. This consisted of approximately 65 thousand tweets in total. I could have collected more data, but twitter has a limit of 5000 tweets in a single download, so it’s quite a faff to collect more. Furthermore, I didn’t think that more tweets from earlier in the day to substantially change the pattern.

The names of the “sentiments” are fixed, sometimes not exactly to my preferred choice; tweets with a high “trust” sentiment are often quite hopeful for example… but that is a whole different problem (and is someone else’s problem to worry about!)

Definitely a more striking ratio of positive to negative tweets.

And the most commonly used words:

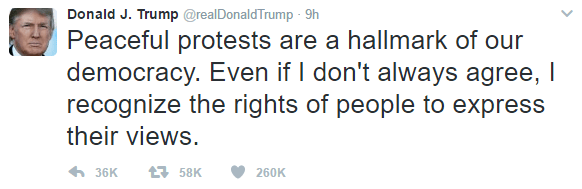

Finally, for those interested in this tweet:

It came from an Android phone on a Sunday (but not very early in the morning / late at night); so those speculating that it was not the man himself tweeting don’t have the obvious indication of it coming from an iPhone!